AP Biology Unit 2 Study Guide: Cell Structure and Function

This comprehensive guide delves into the core principles of cell structure and function, essential for AP Biology success․ Explore organelles, membrane transport, and signaling pathways․

Master key concepts with detailed reviews, aligning with the 2025 AP Biology Course and Exam Description (CED)․ Prepare to ace your exam with focused study!

Utilize flashcards and practice questions to solidify understanding of cellular energetics, anabolic/catabolic pathways, and activation energy․ Become a cell biology expert!

Overview of Unit 2

Unit 2 of AP Biology fundamentally explores the building blocks of life – cells – and their intricate functions․ This unit constitutes approximately 10-13% of the overall AP exam score, making a thorough understanding crucial for success․ Students will investigate the structural components of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, discerning their similarities and differences․

A core focus lies on understanding how cell size impacts functionality, particularly concerning the surface area to volume ratio․ This concept dictates a cell’s ability to efficiently transport materials and communicate with its environment․ Furthermore, the unit delves into the dynamic nature of cell membranes, examining phospholipid bilayers and the diverse roles of membrane proteins in transport mechanisms․

Students will analyze both passive and active transport, including osmosis and water potential, alongside the specialized functions of organelles like the nucleus, ribosomes, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, mitochondria, and chloroplasts․ Finally, the unit introduces cellular communication pathways and the importance of compartmentalization for efficient cellular processes․ Mastering these concepts provides a solid foundation for subsequent units․

Importance of Cell Structure

Cell structure is paramount to understanding life’s processes․ The arrangement of cellular components directly dictates a cell’s function, influencing everything from nutrient uptake to waste removal and reproduction․ A cell’s architecture isn’t arbitrary; it’s a product of evolutionary adaptation, optimized for specific roles within an organism․

Understanding organelles – the nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and others – reveals how cells compartmentalize tasks, increasing efficiency and preventing conflicting reactions․ The cell membrane’s selective permeability, governed by its phospholipid bilayer and protein channels, controls the internal environment, maintaining homeostasis․

Disruptions to cell structure, whether through genetic mutations or environmental factors, can lead to cellular dysfunction and disease․ Therefore, comprehending the intricate relationship between structure and function is vital not only for AP Biology but also for fields like medicine and biotechnology․ Studying cell structure provides a foundational understanding of how life operates at its most basic level, enabling us to address complex biological challenges․

Prokaryotic vs․ Eukaryotic Cells

Distinguishing between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells is fundamental to understanding life’s diversity․ Prokaryotic cells, like bacteria and archaea, lack a membrane-bound nucleus and other complex organelles․ Their DNA resides in a nucleoid region, and they are generally smaller and simpler in structure․

Eukaryotic cells, found in protists, fungi, plants, and animals, possess a true nucleus housing their DNA, along with various membrane-bound organelles like mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum․ This compartmentalization allows for specialized functions and greater cellular complexity․

Key differences extend to cell size, ribosome structure, and the presence of a cell wall․ Prokaryotes typically have a peptidoglycan cell wall, while eukaryotes may have cell walls made of cellulose (plants) or chitin (fungi)․ Understanding these distinctions is crucial for comprehending evolutionary relationships and the unique characteristics of different organisms․ Recognizing these structural differences is essential for success on the AP Biology exam․

Cell Size and Surface Area to Volume Ratio

Cell size is constrained by the surface area to volume ratio (SA:V)․ As a cell increases in size, its volume grows faster than its surface area․ The surface area is critical for nutrient uptake, waste removal, and gas exchange – all vital cellular processes․

A high SA:V ratio, characteristic of smaller cells, facilitates efficient transport of materials across the cell membrane․ Conversely, a low SA:V ratio in larger cells hinders this exchange, limiting their ability to function effectively․ This principle explains why cells remain relatively small․

Cells overcome this limitation through adaptations like cell compartmentalization (organelles) and membrane folding (microvilli)․ These strategies increase surface area without drastically increasing volume․ Understanding the SA:V ratio’s impact on function is crucial for explaining cell shape, size, and overall efficiency․ This concept is frequently tested on the AP Biology exam, so mastery is key!

Cell Components & Structures

Explore eukaryotic cell organelles – nucleus, mitochondria, ER, and Golgi – and their specialized roles․ Understand how these structures work together to maintain cellular life and function․

The Cell Membrane: Structure and Function

The cell membrane is a crucial boundary, selectively controlling substance passage․ It’s a dynamic structure composed primarily of a phospholipid bilayer, providing a flexible matrix․ This bilayer’s arrangement creates a barrier to hydrophilic molecules, while allowing lipid-soluble substances to pass through easily․

Membrane proteins are embedded within this bilayer, performing diverse functions․ Transport proteins facilitate movement across the membrane, while receptor proteins bind signaling molecules initiating cellular responses․ Channel proteins create pores for specific ions, and enzymes catalyze reactions․

Fluid mosaic model describes the membrane’s structure, highlighting the fluidity of the phospholipids and the mosaic of proteins․ This fluidity is vital for membrane function, allowing proteins to move and interact․ The membrane isn’t just a passive barrier; it actively participates in cellular processes, maintaining homeostasis and enabling communication with the external environment․ Understanding its structure is key to grasping transport mechanisms․

Phospholipids and Membrane Fluidity

Phospholipids are the fundamental building blocks of the cell membrane, possessing both hydrophilic (water-attracting) and hydrophobic (water-repelling) regions․ This amphipathic nature drives their self-assembly into a bilayer, with hydrophobic tails facing inward and hydrophilic heads facing outward, interacting with the aqueous environment․

Membrane fluidity, a critical property, refers to the viscosity of the membrane, influenced by temperature and phospholipid composition․ Unsaturated fatty acids introduce kinks, preventing tight packing and increasing fluidity․ Cholesterol acts as a buffer, stabilizing the membrane at varying temperatures – reducing fluidity at high temperatures and preventing solidification at low temperatures․

Fluidity impacts membrane function, enabling protein movement, membrane flexibility, and proper functioning of transport proteins․ It’s essential for processes like cell growth, division, and signaling․ Maintaining optimal fluidity is crucial for cellular health and survival, ensuring the membrane remains a dynamic and effective barrier․

Membrane Proteins: Types and Roles

Membrane proteins are integral or peripheral components embedded within or associated with the cell membrane, performing diverse functions crucial for cellular life․ Integral proteins span the entire membrane, often acting as channels or carriers for facilitated diffusion and active transport․

Peripheral proteins are loosely bound to the membrane surface, playing roles in signaling and structural support․ Transport proteins facilitate the movement of substances across the membrane, while enzymes catalyze reactions․ Receptor proteins bind signaling molecules, initiating cellular responses․

Cell-cell recognition proteins identify cells, and junction proteins connect cells together․ These proteins aren’t static; they move laterally within the membrane, contributing to its fluidity and dynamic function․ Their specific arrangement and interactions are vital for maintaining cellular integrity and carrying out essential processes․

Passive Transport Mechanisms

Passive transport relies on the concentration gradient to move substances across the cell membrane, requiring no cellular energy expenditure․ Diffusion is the movement of molecules from an area of high concentration to low concentration, driven by entropy․ Facilitated diffusion utilizes transport proteins to assist the passage of molecules that cannot directly cross the lipid bilayer․

Channel proteins create hydrophilic pathways, while carrier proteins bind to the solute and change conformation․ Osmosis, a specific type of diffusion, focuses on water movement across a semi-permeable membrane, influenced by water potential․ These mechanisms are vital for nutrient uptake and waste removal․

Understanding these processes is key to grasping cellular homeostasis․ Factors like temperature and molecule size influence the rate of passive transport, impacting cellular function and overall organismal health․

Active Transport Mechanisms

Active transport moves substances against their concentration gradient, requiring cellular energy, typically in the form of ATP․ Sodium-potassium pumps are a prime example, maintaining electrochemical gradients essential for nerve impulse transmission and muscle contraction․ These pumps utilize ATP hydrolysis to move ions․

Co-transport leverages the gradient established by one active transport protein to drive the movement of another․ Symport moves both substances in the same direction, while antiport moves them in opposite directions․ Endocytosis and exocytosis involve bulk transport via vesicle formation․

Endocytosis brings materials into the cell (phagocytosis & pinocytosis), while exocytosis releases materials from the cell․ These processes are crucial for cellular communication, nutrient acquisition, and waste elimination, demonstrating the cell’s dynamic nature․

Water Potential and Osmosis

Water potential (Ψ) measures the relative tendency of water to move from one area to another․ It’s influenced by solute potential (Ψs) – decreased by solute concentration – and pressure potential (Ψp) – increased by physical pressure․ Pure water at sea level has a Ψ of zero․

Osmosis is the diffusion of water across a selectively permeable membrane, driven by differences in water potential․ Water moves from areas of high water potential (low solute concentration) to areas of low water potential (high solute concentration)․ This movement continues until equilibrium is reached․

Understanding tonicity – hypotonic, hypertonic, and isotonic solutions – is crucial․ Cells in hypotonic solutions gain water, potentially lysing; in hypertonic solutions, they lose water, potentially crenating․ Isotonic solutions maintain equilibrium․ Water potential profoundly impacts plant cell turgor pressure and animal cell volume․

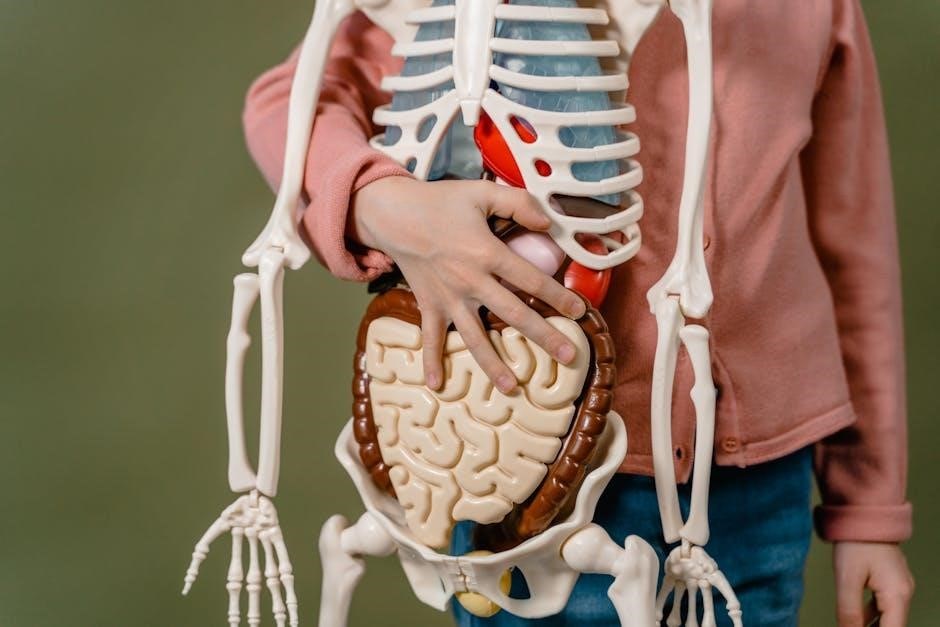

Organelles and Their Functions

Explore eukaryotic cell structures – nucleus, ribosomes, ER, Golgi, lysosomes, vacuoles, mitochondria, and chloroplasts – each performing specialized tasks․ Understand their roles in cellular processes!

Master organelle functions to grasp cellular compartmentalization and efficient operation․ This knowledge is vital for excelling in AP Biology․

The Nucleus: Genetic Control Center

The nucleus reigns supreme as the cell’s genetic command center, housing the DNA organized into chromosomes․ This vital organelle dictates cellular activities through gene expression, controlling protein synthesis and ultimately, cell function․ Its double membrane, the nuclear envelope, safeguards the genetic material and regulates transport via nuclear pores․

Within the nucleus, chromatin – a complex of DNA and proteins – condenses into visible chromosomes during cell division․ The nucleolus, a prominent structure inside, is responsible for ribosome subunit assembly, crucial for protein production․ Understanding the nucleus’s structure and function is paramount for grasping heredity and cellular regulation․

AP Biology students must comprehend how DNA replication and transcription occur within the nucleus, initiating the flow of genetic information․ Errors in these processes can lead to mutations and cellular dysfunction․ The nucleus isn’t just a storage site; it’s a dynamic hub of genetic activity, essential for life’s processes․

Furthermore, the nucleus communicates with the cytoplasm, coordinating cellular events․ Its integrity is vital for maintaining genomic stability and ensuring proper cell function․ A malfunctioning nucleus can have devastating consequences for the cell and the organism․

Ribosomes: Protein Synthesis

Ribosomes are the cellular workhorses dedicated to protein synthesis, translating genetic code into functional proteins․ These aren’t membrane-bound organelles, existing as complexes of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and proteins․ They’re found free-floating in the cytoplasm or bound to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), forming rough ER․

The process unfolds in three key stages: initiation, elongation, and termination․ Messenger RNA (mRNA) carries genetic instructions from the nucleus to the ribosome, where transfer RNA (tRNA) delivers corresponding amino acids․ These amino acids link together, forming polypeptide chains – the building blocks of proteins․

AP Biology students must understand the structural differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic ribosomes, impacting antibiotic targeting․ Ribosomal function is crucial for all cellular processes, from enzyme catalysis to structural support․ Errors in translation can lead to non-functional proteins and disease․

Essentially, ribosomes are the sites where the genetic code is decoded and brought to life, creating the proteins that drive cellular activity․ Their efficiency and accuracy are vital for maintaining cellular health and organismal function․

Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER): Rough and Smooth

The Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) is an extensive network of membranes forming compartments within eukaryotic cells․ It exists in two primary forms: rough ER and smooth ER, each with distinct structures and functions crucial for cellular operation․

Rough ER (RER) is studded with ribosomes, giving it a “rough” appearance․ Its primary role is protein synthesis and modification, particularly for proteins destined for secretion or membrane integration․ These proteins fold and undergo quality control within the RER lumen․

Smooth ER (SER) lacks ribosomes and is involved in lipid synthesis, carbohydrate metabolism, and detoxification of drugs and poisons․ SER also stores calcium ions, vital for muscle contraction and signaling․

AP Biology students should understand how the ER’s structure directly relates to its function․ The extensive surface area provided by the ER membranes maximizes efficiency in these processes․ Proper ER function is essential for cellular homeostasis and overall organismal health․

Golgi Apparatus: Processing and Packaging

The Golgi Apparatus, often described as the “post office” of the cell, is a central organelle responsible for processing and packaging macromolecules, particularly proteins and lipids․ It receives vesicles containing these molecules from the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER)․

Structurally, the Golgi consists of flattened, membrane-bound sacs called cisternae, arranged in stacks․ Molecules move through the Golgi, undergoing modifications like glycosylation (adding sugars) and phosphorylation․ These modifications act as “address labels” directing proteins to their final destinations․

The Golgi packages modified molecules into vesicles for transport․ These vesicles can be targeted to various locations: the plasma membrane for secretion, lysosomes for degradation, or other organelles․

For AP Biology, understanding the Golgi’s role in protein trafficking and modification is key․ Its efficient processing and packaging are vital for cellular function and communication․ Visualize the Golgi as a dynamic hub ensuring proper delivery of cellular products․

Lysosomes: Cellular Digestion

Lysosomes are membrane-bound organelles functioning as the primary digestive system within the cell․ They contain hydrolytic enzymes capable of breaking down a wide range of macromolecules – proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids․

These enzymes work best in an acidic environment, maintained within the lysosome․ Lysosomes fuse with vesicles containing cellular waste, damaged organelles (autophagy), or engulfed materials (phagocytosis) to initiate degradation․

Autophagy is crucial for cellular renewal, removing old or dysfunctional components․ Phagocytosis, common in immune cells, allows for the destruction of foreign invaders like bacteria․ The resulting monomers are then recycled for building new molecules․

For AP Biology, recognize lysosomes as essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis․ Defects in lysosomal function can lead to various storage diseases․ Understanding their role in degradation and recycling is vital for comprehending cellular processes․

Vacuoles: Storage and Support

Vacuoles are large, membrane-bound sacs within cells serving diverse storage and structural roles․ Their functions vary significantly depending on the cell type, particularly between plant and animal cells․

In plant cells, the central vacuole is prominent, storing water, ions, pigments, and waste products․ It maintains turgor pressure against the cell wall, providing structural support․ This pressure is essential for plant rigidity and preventing wilting․

Animal cells typically have smaller, more numerous vacuoles used for temporary storage of nutrients, ions, and waste․ They also participate in exocytosis and endocytosis, transporting materials in and out of the cell․

For AP Biology, understand vacuoles as dynamic organelles crucial for maintaining cell volume, regulating cytoplasmic composition, and contributing to overall cellular homeostasis․ Consider their role in detoxification and pigment storage․

Mitochondria: Cellular Respiration

Mitochondria are often called the “powerhouses of the cell” due to their central role in cellular respiration․ These double-membrane bound organelles generate most of the cell’s ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the primary energy currency․

The inner mitochondrial membrane is highly folded into cristae, increasing surface area for ATP production․ Cellular respiration involves a series of metabolic pathways – glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and the electron transport chain – occurring within specific mitochondrial compartments․

ATP synthesis relies on oxidative phosphorylation, utilizing the proton gradient established across the inner membrane․ Understanding the structure-function relationship of mitochondria is crucial for AP Biology․

For exam preparation, focus on the inputs and outputs of each stage of cellular respiration, and how mitochondria contribute to overall energy production․ Remember their unique genetic material and endosymbiotic origin!

Chloroplasts: Photosynthesis (Plant Cells)

Chloroplasts are the sites of photosynthesis in plant cells, converting light energy into chemical energy in the form of glucose․ Like mitochondria, they possess a double membrane structure, but also contain internal stacks of thylakoids called grana․

Photosynthesis occurs in two main stages: the light-dependent reactions (in the thylakoid membranes) and the light-independent reactions (Calvin cycle, in the stroma)․ These processes utilize chlorophyll and other pigments to capture light energy․

Understanding the inputs (carbon dioxide, water, light) and outputs (glucose, oxygen) of photosynthesis is vital for AP Biology․ Focus on the role of chloroplasts in energy production and their evolutionary origins․

For exam success, master the relationship between chloroplast structure and photosynthetic function․ Remember the importance of chlorophyll and the impact of environmental factors on photosynthetic rates!

Cellular Processes

Explore vital processes like cell communication, the cell cycle, and mitosis․ Understand how compartmentalization enhances efficiency and how membrane transport regulates cellular environments․

Master these concepts to grasp the dynamic nature of cells and their interactions, crucial for AP Biology exam success!

Cell Communication: Signaling Pathways

Cellular communication is paramount for coordinated function in multicellular organisms․ This involves intricate signaling pathways that allow cells to detect and respond to their environment․ These pathways typically begin with a signaling molecule – a ligand – binding to a receptor protein, often located on the cell surface․

Signal transduction then occurs, converting the extracellular signal into an intracellular response․ This often involves a cascade of protein modifications, like phosphorylation, amplifying the signal․ Common signaling pathways include those utilizing G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), and ligand-gated ion channels․

Understanding these pathways is crucial, as disruptions can lead to various diseases․ Responses can be rapid, like ion channel opening, or slower, involving changes in gene expression․ Furthermore, pathways can be terminated through feedback mechanisms, ensuring appropriate signaling duration․ AP Biology emphasizes the importance of recognizing these key components and their roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis and organismal function․

Key terms to master include signal, receptor, transduction, response, and amplification․ Knowing how different signaling pathways operate and their potential consequences is vital for exam success․

Cell Cycle and Mitosis

The cell cycle is a highly regulated series of events leading to cell growth and division․ It consists of interphase (G1, S, and G2 phases) and the mitotic (M) phase․ Interphase prepares the cell for division, including DNA replication during the S phase․ The M phase encompasses mitosis and cytokinesis․

Mitosis, the process of nuclear division, is divided into prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase (PMAT)․ During prophase, chromosomes condense, and the mitotic spindle forms․ Metaphase sees chromosomes align at the metaphase plate․ Anaphase involves sister chromatid separation, and telophase culminates in two distinct nuclei․

Cytokinesis, the division of the cytoplasm, typically occurs concurrently with telophase․ AP Biology requires understanding the role of checkpoints within the cell cycle, ensuring accurate DNA replication and chromosome segregation․ Errors can lead to uncontrolled cell growth and potentially cancer․ Mastering the stages of mitosis and their associated events is essential for exam success․

Key concepts include chromosome structure, spindle fiber function, and the significance of checkpoints in maintaining genomic integrity․

Cellular Compartmentalization

Cellular compartmentalization is a fundamental principle of eukaryotic cell structure, wherein internal membranes create distinct organelles․ These organelles provide specialized environments for specific cellular processes, enhancing efficiency and preventing interference․

Organelles like the nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and mitochondria each house unique sets of enzymes and molecules․ This segregation allows for incompatible reactions to occur simultaneously within the same cell․ For example, hydrolytic enzymes of lysosomes are contained to prevent self-digestion․

Compartmentalization increases the surface area for reactions, concentrating substrates and enzymes․ It also establishes specific pH levels and ion concentrations optimal for particular functions․ Understanding how this organization contributes to cellular function is crucial for AP Biology․

Membrane permeability regulates the movement of substances between compartments, maintaining distinct internal conditions․ This concept is vital for understanding processes like protein sorting and signal transduction․ Mastering this principle is key to understanding complex cellular processes․

Membrane Transport in Detail

Membrane transport governs the movement of substances across the cell membrane, crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis․ This process is categorized into passive and active transport mechanisms, each with distinct characteristics․

Passive transport, including diffusion, osmosis, and facilitated diffusion, requires no energy expenditure․ Substances move down their concentration gradient, from high to low concentration․ Osmosis, specifically, involves water movement across a semi-permeable membrane, influenced by water potential․

Active transport, conversely, requires energy (typically ATP) to move substances against their concentration gradient․ This includes processes like proton pumps and cotransport․ Understanding the role of membrane proteins in both passive and active transport is essential․

Water potential is a key concept in osmosis, impacting cell turgor pressure and overall cellular function․ Mastering these transport mechanisms is vital for AP Biology, as they underpin numerous biological processes and cellular interactions․

Surface Area to Volume Ratio Impact on Function

The surface area to volume ratio (SA:V) is a critical factor influencing cell size and function․ As a cell increases in size, its volume grows faster than its surface area․ This impacts the cell’s ability to efficiently exchange materials with its environment․

A high SA:V ratio, characteristic of smaller cells, facilitates rapid transport of nutrients and waste․ This is essential for processes like gas exchange and nutrient uptake․ Conversely, a low SA:V ratio, found in larger cells, hinders efficient exchange․

Cell compartmentalization, through organelles, effectively increases the total surface area available for reactions within the cell․ This overcomes the limitations imposed by a decreasing SA:V ratio as cell size increases․

Understanding this relationship is fundamental to grasping cellular limitations and adaptations․ It explains why cells remain relatively small and why specialized structures like microvilli enhance surface area for absorption, crucial for AP Biology comprehension․